Book Review The People’s Pictures Photographs by Lee Friedlander Reviewed by Blake Andrews “If you want to portray the American Dream in just one picture, you could do worse than the cover photo of Gillian Laub’s new monograph Family Matters. It shows Laub’s late grandfather Irving Yasgur, engaged with a large cheeseburger and fries. It’s his 85th birthday in 2003 and he’s enjoying the fruits of a long self-made journey into wealthy retirement… »

Photographs by Lee Friedlander

Eakins Press Foundation, New York, NY 2021. 168 pp., 147 illustrations, 11½x12″.

In perhaps his most famous anecdote, Lee Friedlander once described an early experience aiming his camera at a scene before him. “I only wanted Uncle Vern standing by his new car (a Hudson) on a clear day,” he remembers. “I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on a fence, and a row of potted tuberous begonias on the porch and seventy-eight trees and a million pebbles in the driveway and more. It’s a generous medium, photography.”

The rest, as they say, is history. Sparked in part by that a-ha moment, Friedlander went on to have a prolific career making pictures and books. He’s photographed in every state and several countries, published more than fifty monographs, and he’s still going strong at 87. Through it all his visual appetite has remained supple, feasting at one time or another on virtually every subject imaginable, from cherry blossoms to factories to nudes, flower stems, pedestrians and friends. The popular legend is that he keeps a separate cardboard box for each subject. Occasionally a box results in a monograph. Until then they are open for receiving. He pays no mind to category while shooting. It’s only later that he sorts prints into whatever box is most suitable. Shoot first, ask questions later, repeat as necessary. A generous medium indeed.

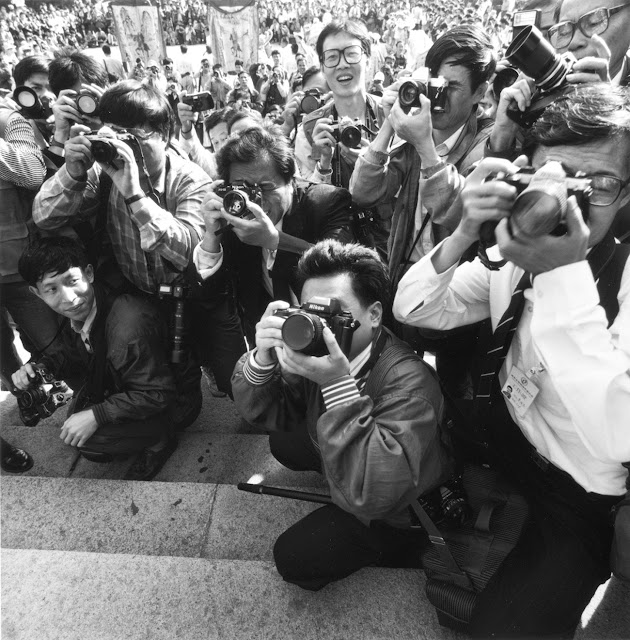

As it turns out, one of those boxes held photos of amateur photographers. Friedlander witnessed other shutterbugs regularly in the course of his own wanderings. Film cameras were once commonplace, and they were more photogenic than smartphones. He encountered them being used at public events or landmarks, and sometimes just snapping candids in the kitchen. Most of these photographers were oblivious to him. They were just trying to catch their own bit of Uncle Vern without too much laundry or dog. Friedlander patiently captured them all, just as he did everything in his path. With a few notable exceptions, most have remained unpublished until now.

|

|

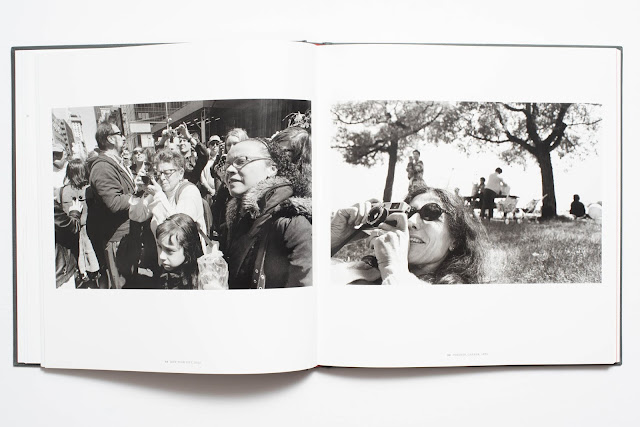

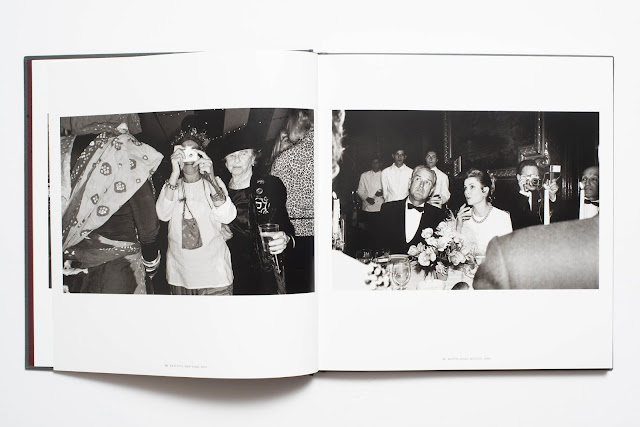

The latest Friedlander monograph from Eakins Press brings several dozen into the public realm, under the fitting title, The People’s Pictures. In typical Eakins fashion, they are reproduced as impeccable duotones, and collected in a large handsome hardback. It’s a monograph intended for posterity as much as for current readers, a sort of love letter to the act of photography, a capstone to a lifetime of devotion. These pictures of picture-making cover a range of places and dates. They’re sequenced in scattered fashion, hopscotching from place to place, and back and forth from the 1960s to the 2010s. The heaviest emphasis is on the 70s and 80s, perhaps the glory days of a certain style of amateur camera, and the glory days for Friedlander’s own 35 mm forays, before he moved on to the Hassy Superwide.

Friedlander’s visual appetite has always been voracious, but the energy of youth and the freewheeling spirit of the ‘70s elevated him into a special zone during that period. Alongside the mundane social landscapes for which he is perhaps best known, he photographed a seemingly non-stop series of populated events, shows, parties, marches, and speeches. At most of these events were amateurs with cameras, so he obligingly shot them too.

|

It’s hard to know his exact intentions, but they seem partially motivated by the fact of presence. These photographers were simply there, like Everest. But it’s tempting to read another motivation into his frames: Friedlander’s affinity for the photographic act. Some of the photos peer right over the shoulder of another photographer, as if Friedlander is stepping into their shoes, to soak up some of that good photo feeling vicariously. He’s inches from the primordial act, the bliss of photographic conception. Thumbing The People’s Pictures, one feels the intimacy and immediacy of exposure, the sheer joy of pointing a camera at something, and the anticipation of what it might look like. All have been driving forces throughout Friedlander’s creative life. In these pictures they pull in the same direction for a split second.

But of course, Friedlander being Friedlander, no picture is quite what it first appears to be. A photo of a woman shooting a Leica in a crowd might be a portrait of her. But the frame seems equally concerned with the surrounding faces. Another shutterbug in New Orleans, squatting to frame a scene, might be just be the thing that caught Friedlander’s attention. But it’s hard to say. The surrounding onlookers demand visual attention too. A shot from Thailand blends photographer, arm, and background pagoda into a layered monochrome with impish fun, as does a strangely blended scene from Colorado Springs. All manifest Friedlander’s “mischievous but fundamentally rigorous and unforgiving style,” as once described by the New York Times .

|

Maybe it’s just me, but these photos seem to possess an outsized Uncle Vern quality which is noteworthy even for Friedlander. That is, they capture not just the primary subject but a wealth of background details, ephemera, and raw information. There is so much pure content to digest in these pictures. Each one is a visual buffet spilling over. It’s a generous medium indeed. And it has been very generous to Lee Friedlander.

Looking at the meta-pictures in this book — pictures of picture-making, essentially — it’s tantalizing to wonder how all those amateur snapshots turned out. It would be wonderful to match them with Friedlander’s photos into a sort of Cubist multi-perspective take on the original scenes.

|

That’s impossible, of course. Friedlander’s quick impressions must suffice—Not such a bad thing! But for those antsy to see results of some sort, the last third of the book takes a step in that direction. The images switch over from public image-makers to public images, with an assortment of snapshots, posters, signs, and other photographic material found and shot by Friedlander. Windows, shops, billboards, and that sort of thing. For long-time Friedlander fans, this section will seem more familiar than the first. It’s very typical of his quiet, patient, and somewhat forlorn style. This latter section is entertaining — just as all Friedlander photos are — and a nice visual rejoinder to the first half. But it is less populated and closer to the known wheelhouse, and for me less novel. But I’ll take it, just as I’ll take the entire book (and the next one too, if and when it comes). It’s hard to pick a favorite from Friedlander’s countless monographs, but this one is highlight among recent titles. A love letter to the photographic act, it should resonate with all the other lovers.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

|

|

|

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.